Urethroplasty for Pelvic Fracture Urethral Injury (PFUI)

Figure 1: In the normal male pelvis, the prostate is connected to the pelvic bone (pubis) by a ligament (in pink).

bladder

pelvic bone

rectum

prostate

Puboprostatic ligament

front

back

Figure 1:

Figure 2: This following descriptions and illustrations feature one type of pelvic fracture. Although there are many variations of pelvic fracture and they can each affect the urethra differently, these images tell a pretty typical story. The pelvic bone is fractured, and as the two pieces of bone move independently from each other, the parts of the urinary system that are attached to them will also move independently. Therefore the prostate and upper urethra can be torn from the the lower urethra.

bladder

pelvic bone

rectum

prostate

Puboprostatic ligament

Figure 2:

Figure 3: In the first few days after the accident, the broken bones and other torn tissues will bleed and form a large clot, we call a hematoma (shown in maroon). That hematoma will eventually turn into scar tissue as the tissues heal. Only an outline of the bones is shown here so that you can see the other things behind them.

In the emergency situation we must get the urine drained from the bladder. There are two ways of doing this. Either a catheter can be placed through the skin on the lower abdomen, directly into the bladder (we call this a suprapubic tube and it is shown here) or doctors can try to get a catheter from the lower urethra, across the hematoma, and into the bladder using camera scopes and x-rays.

bladder

rectum

subrapubic tube

prostate

Figure 3:

Figure 4: If a catheter is fished across the hematoma successfully then the hematoma will later form a scar tissue around the catheter (shown in green).

bladder

rectum

subrapubic tube

prostate

Figure 4:

Figure 5: As soon as the urethral catheter is removed, the area where the catheter was located will fill in with scar (shown in green).

Whether we only place a suprapubic catheter or we get a catheter to fish from the lower urethra to the upper urethra and into the bladder, all of these urethras will eventually be blocked by scar tissue.

Some doctors will try to stretch this scar tissue but that is not recommended. There is so much unhealthy tissue in that area that stretching of the scar is never successful. The scar must be removed and the urethral ends reconnected.

bladder

rectum

subrapubic tube

prostate

Figure 5:

Figure 6: In a urethroplasty for pelvic fracture urethral injury, an incision is made in the perineum, which is the area between the scrotum (testicle sack) and the rectum.

bladder

rectum

subrapubic tube

prostate

Figure 6:

Figure 7: The urethra is divided where it meets the scar tissue (red dotted line). The lower urethra is then dissected from its surrounding structures all the way to where the urethra enters the beginning of the penis. This will give the urethra some flexibility to be able to stretch to reach the upper urethra.

bladder

rectum

subrapubic tube

prostate

Figure 7:

Figure 8: The scar tissue is removed. Sometimes this requires removing a little bit of the bone (this does not cause any problems later).

bladder

rectum

subrapubic tube

prostate

Figure 8:

Figure 9: The edges of the two ends of the urethra are freshened up so that they will connect back together nicely, with no scar. You can see in the figure that unhealthy/scarred urethral ends are removed until the edges are pink and healthy.

bladder

rectum

subrapubic tube

prostate

Figure 9:

Figure 10: The two ends of the urethra are sewn together and the skin is closed. We will usually leave a catheter in the penis for 1 month.

bladder

rectum

prostate

Figure 10:

Figure 11: Although most injuries are not this bad, here is an example of a very difficult urethral injury that Dr. Elliott repaired using a urethroplasty.

6 cm (3 in) gap

bladder

urethra

Before

Figure 11a:

bladder

reconnection

urethra

After

Figure 11b:

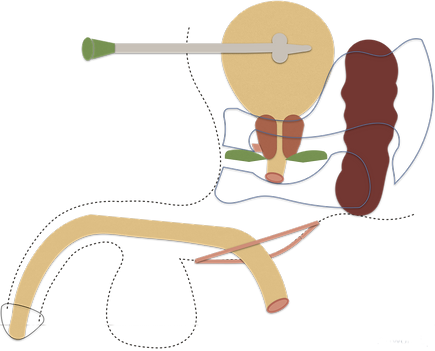

Figure 12: When the distance between the two ends of the urethra is very long (as in Figure 11 x-ray, above) this is because the prostate and bladder have been torn from their usual location at the bottom of the pelvis and lifted up and away from the lower urethra. Notice that in this illustration (as in the x-ray in Figure 11a), the prostate is above the broken pelvic bone, meaning it is up in the abdomen instead of down in the pelvis.

Figure 12:

Figure 13: The hematoma (in maroon on Figure 12) will solidify in scar (in green on Figure 13).

In this case, we cannot remove all of the scar tissue through an incision between the legs ("from below"); the scar tissue extends so high into the abdomen that we have to remove some scar from above, and some from below.

We perform the abdominal part of the operation using a robot and several pencil-sized instruments through a few small holes in the abdomen.

Figure 13:

Figure 14: Using the robotic scissors, we remove the scar tissue, revealing the healthy prostate and urethra under the scar.

Figure 14:

Figure 15: Once all the scar is removed, we move the bladder and prostate back down into the pelvis where they belong. This sets us up to the reconnect the prostate end of the urethra to the penis end of the urethra.

Figure 15:

Figure 16: The two ends of the urethra are then sewn back together again using the robot.

Figure 16: